- Review

- Open access

- Published:

A review of academic literacy research development: from 2002 to 2019

Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education volume 7, Article number: 5 (2022)

Abstract

Academic literacy as an embodiment of higher-order language and thinking skills within the academic community bears huge significance for language socialization, resource distribution and even power disposition within the larger sociocultural context. However, although the notion of academic literacy has been initiated for more than twenty years, there still lacks a clear definition and operationalization of the construct. The study conducted a systematic review of academic literacy research based on 94 systematically selected research papers on academic literacy from 2002 to 2019 from multiple databases. These papers were then coded respectively in terms of their research methods, types (interventionistic or descriptive), settings and research focus. Findings demonstrate (1) the multidimensionality of academic literacy construct; (2) a growing number of mixed methods interventionistic studies in recent years; and (3) a gradual expansion of academic literacy research in ESL and EFL settings. These findings can inform the design and implementation of future academic literacy research and practices.

Introduction

Academic literacy as an embodiment of higher order thinking and learning not only serves as a prerequisite for knowledge production and communication within the disciplines but also bears huge significance for individual language and cognitive development (Flowerdew, 2013; Moje, 2015). Recent researches on academic literacy gradually moved from regarding literacy as discrete, transferrable skills to literacy as a social practice, closely associated with disciplinary epistemology and identity (Gee, 2015). The view of literacy learning as both a textual and contextual practice is largely driven by the changing educational goal under the development of twenty-first century knowledge economy, which requires learners to be active co-constructors of knowledge rather than passive recipients (Gebhard, 2004). Academic literacy development in this sense is considered as a powerful tool for knowledge generation, communication and transformation.

However, up-till-now, there still seems to lack a clear definition and operationalization of the academic literacy construct that can guide effective pedagogy (Wingate, 2018). This can possibly lead to a peril of regarding academic literacy as an umbrella term, with few specifications on the potential of the construct to afford actual teaching and learning practices. In this sense, a systematic review in terms of how the construct was defined, operationalized and approached in actual research settings can embody huge potential in bridging the gap between theory and practice.

Based on these concerns, the study conducts a critical review of academic literacy research over the past twenty years in terms of the construct of the academic literacy, their methods, approaches, settings and keywords. A mixed methods approach is adopted to combine qualitative coding with quantitative analysis to investigate diachronic changes. Results of the study can enrich the understandings of the construct of academic literacy and its relations to actual pedagogical practices while shedding light on future directions of research.

Literature review

Academic literacy as a set of literacy skills specialized for content learning is closely associated with individual higher order thinking and advanced language skill development (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). Recent researches suggest that the development of the advanced literacy skills can only be achieved via students’ active engagement in authentic and purposeful disciplinary learning activities, imbued with meaning, value and emotions (Moje et al., 2008). Therefore, contrary to the ‘autonomous model’ of literacy development which views literacy as a set of discrete, transferrable reading and writing skills, academic literacy development is viewed as participation, socialization and transformation achieved via individual’s expanding involvement in authentic and meaningful disciplinary learning inquiries (Duff, 2010; Russell, 2009). Academic literacy development in this sense is viewed as a powerful mediation for individual socialization into the academic community, which is in turn closely related to issues of power disposition, resource distribution and social justice (Broom, 2004). In this sense, academic literacy development is by no means only a cognitive issue but situated social and cultural practices widely shaped by power, structure and ideology (Lillis & Scott, 2007; Wenger, 1998).

The view of literacy learning as a social practice is typically reflected in genre and the ‘academic literacies’ model. Genre, as a series of typified, recurring social actions serves as a powerful semiotic tool for individuals to act together meaningfully and purposefully (Fang & Coatoam, 2013). Academic literacy development in this sense is viewed as individual’s gradual appropriation of the shared cultural values and communicative repertoires within the disciplines. These routinized practices of knowing, doing and being not only serve to guarantee the hidden quality of disciplinary knowledge production but also entail a frame of action for academic community functioning (Fisher, 2019; Wenger, 1998). Therefore, academic literacy development empowers individual thinking and learning in pursuit of effective community practices.

Complementary to the genre approach, the ‘academic literacies’ model “views student writing and learning as issues at the level of epistemology and identities rather than skill or socialization” from the lens of critical literacy, power and ideology (Lea & Street, 1998, p. 159). Drawing from ‘New Literacies’, the ‘academic literacies’ model approaches literacy development within the power of social discourse with the hope to open up possibilities for innovations and change (Lea & Street, 2006). Academic literacy development in this sense is regarded as a powerful tool for access, communication and identification within the academic community, and is therefore closely associated with issues of social justice and equality (Gee, 2015).

The notion of genre and ‘academic literacies’ share multiple resemblances with English for Academic Purposes (EAP), which according to Charles (2013, p. 137) ‘is concerned with researching and teaching the English needed by those who use the language to perform academic tasks’. As can be seen, both approaches regard literacy learning as highly purposeful and contextual, driven by the practical need to ‘foregrounding the tacit nature of academic conventions’ (Lillis & Tuck, 2016, p. 36). However, while EAP is more text-driven, ‘academic literacies’ are more practice-oriented (Lillis & Tuck, 2016). That is rather than focusing on the ‘normative’ descriptions of the academic discourse, the ‘academic literacies’ model lays more emphasis on learner agency, personal experiences and sociocultural diversity, regarded as a valuable source for individual learning and the transformation of community practices (Lillis & Tuck, 2016). This view of literacy learning as meaningful social participation and transformation is now gradually adopted in the approach of critical EAP (Charles, 2013).

In sum, all these approaches regard academic literacy development as multi-dimensional, encompassing both linguistic, cognitive and sociocultural practices (Cumming, 2013). However, up-till-now, there still seems to lack a clear definition and operationalization of the academic literacy construct that can guide concrete pedagogies. Short and Fitzsimmons (2007, p. 2) provided a tentative definition of academic literacy from the following aspects:

Includes reading, writing, and oral discourse for school

Varies from subject to subject

Requires knowledge of multiple genres of text, purposes for text use, and text media

Is influenced by students’ literacies in contexts outside of school

Is influenced by students’ personal, social, and cultural experiences.

This definition has specified the main features of academic literacy as both a cognitive and sociocultural construct; however, more elaborations may be needed to further operationalize the construct in real educational and research settings. Drawing from this, Allison and Harklau (2010) and Fang (2012) specified three general approaches to academic literacy research, namely: the language, cognitive (disciplinary) and the sociocultural approach, which will be further elaborated in the following.

The language-based approach is mainly text-driven and lays special emphasis on the acquisition of language structures, skills and functions characteristic of content learning (Allison & Harklau, 2010, p. 134; Uccelli et al., 2014), and highlights explicit instruction on academic language features and discourse structures (Hyland, 2008). This notion is widely influenced by Systemic Functional Linguistics which specifies the intricate connections between text and context, or linguistic choices and text meaning-making potential under specific communicative intentions and purposes (Halliday, 2000). This approach often highlights explicit consciousness-raising activities in text deconstruction as embodied in the genre pedagogy, facilitated by corpus-linguistic research tools to unveil structures and patterns of academic language use (Charles, 2013).

One typical example is data driven learning (DDL) or ‘any use of a language corpus by second or foreign language learners’ (Anthony, 2017, p. 163). This approach encourages ‘inductive, self-directed’ language learning under the guidance of the teacher to examine and explore language use in real academic settings. These inquiry-based learning processes not only make language learning meaningful and purposeful but also help form more strategic and autonomous learners (Anthony, 2017).

In sum, the language approach intends to unveil the linguistic and rhetorical structure of academic discourse to make it accessible and available for reflection. However, academic literacy development entails more than the acquisition of academic language skills but also the use of academic language as tool for content learning and scientific reasoning (Bailey et al., 2007), which is closely connected to individual cognitive development, knowledge construction and communication within the disciplines (Fang, 2012).

Therefore, the cognitive or disciplinary-based approach views academic literacy development as higher order thinking and learning in academic socialization in pursuit of deep, contextualized meaning (Granville & Dison, 2005). This notion highlights the cognitive functions of academic literacy as deeply related to disciplinary epistemologies and identities, widely shaped by disciplinary-specific ways of knowing, doing and thinking (Moje, 2015). Just as mentioned by Shanahan (2012, p. 70), ‘approaching a text with a particular point of view affects how individuals read and learn from texts’, academic literacy development is an integrated language and cognitive endeavor.

One typical example in this approach is the Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach (CALLA) initiated by Chamot and O’Malley (1987), proposing the development of a curriculum that integrates mainstream content subject learning, academic language development and learning strategy instruction. This approach embeds language learning within an authentic, purposeful content learning environment, facilitated by strategy training. Another example is the Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol (SIOP model) developed by Echevarría et al. (2013). Sheltered instruction, according to Short et al. (2011, p. 364) refers to ‘a subject class such as mathematics, science, or history taught through English wherein many or all of the students are second language learners’. This approach integrates language and content learning and highlights language learning for subject matter learning purposes (Allison & Harklau, 2010). To make it more specifically, the SIOP model promotes the use of instructional scaffolding to make content comprehensible while advancing students’ skills in a new language (Echevarría et al., 2013, p. 18). Over the decade, this notion integrating language and cognitive development within the disciplines has gradually gained its prominence in bilingual and multilingual education (Goldenberg, 2010).

Complementary to the language and cognitive approach, the sociocultural approach contends literacy learning as a social issue, widely shaped by power, structure and ideology (Gee, 2015; Lea & Street, 2006). This approach highlights the role of learner agency and identity in transforming individual/community learning practices (Lillis & Scott, 2007). Academic literacy in this sense is viewed as a sociocultural construct imbued with meaning, value and emotions as a gateway for social access, power distribution and meaning reconstruction (Moje et al., 2008).

However, despite the various approaches to academic literacy teaching and learning, up-till-now, there still seems to be a paucity of research that can integrate these dimensions into effective intervention and research practices. Current researches on academic literacy development either take an interventionistic or descriptive approach. The former usually takes place within a concrete educational setting under the intention to uncover effective community teaching and learning practices (Engestrom, 1999). The later, on the contrary, often takes a more naturalistic or ethnographic approach with the hope to provide an in-depth account of individual/community learning practices (Lillis & Scott, 2007). These descriptions are often aligned to larger sociocultural contexts and the transformative role of learner agency in collective, object-oriented activities (Engeström, 1987; Wenger, 1998).

These different approaches to academic literacy development are influenced by the varying epistemological stances of the researcher and specific research purposes. However, all these approaches have pointed to a common conception of academic literacy as a multidimensional construct, widely shaped by the sociocultural and historical contexts. This complex and dynamic nature of literacy learning not only enables the constant innovation and expansion of academic literacy construct but also opens up the possibilities to challenge the preconceived notions of relevant research and pedagogical practices.

Based on these concerns, the study intends to conduct a critical review of the twenty years’ development of academic literacy research in terms of their definition of the academic literacy construct, research approaches, methodologies, settings and keywords with the hope to uncover possible developmental trends in interaction. Critical reflections are drawn from this systematic review to shed light on possible future research directions.

Through this review, we intended the address the following three research questions:

-

1.

What is the construct of academic literacy in different approaches of academic literacy research?

-

2.

What are the possible patterns of change in term of academic literacy research methods, approaches and settings over the past twenty years?

-

3.

What are the main focuses of research within each approach of academic literacy development?

Methodology

The study adopts mixed methods to provide a systematic review of academic literacy research over the past twenty years. The rationale for choosing a mixed method is to integrate qualitative text analysis on the features of academic literacy research with quantitative corpus analysis applied on the initial coding results to unveil possible developmental trends.

Inclusion criteria

To locate academic literacy studies over the past twenty years, the researcher conducted a keyword search of ‘academic literacy’ within a wide range of databases within the realm of linguistic and education. For quality control, only peer-reviewed articles from the Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science) were selected. This initial selection criteria yielded 127 papers containing a keyword of ‘academic literacy’ from a range of high-quality journals in linguistics and education from a series of databases, including: Social Science Premium Collection, ERIC (U.S. Dept. of Education), ERIC (ProQuest), Taylor & Francis Online—Journals, Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts, Informa—Taylor & Francis (CrossRef), Arts & Humanities Citation Index (Web of Science), ScienceDirect Journals (Elsevier), ScienceDirect (Elsevier B.V.), Elsevier (CrossRef), ProQuest Education Journals, Sage Journals (Sage Publications), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, JSTOR Archival Journals, Wiley Online Library etc. Among these results, papers from Journal of Second Language Writing, Language and Education, English for Specific Purposes, Teaching in Higher Education, Journal of English for Academic Purposes and Higher Education Research & Development are among the most frequent.

Based on these initial results, the study conducted a second-round detailed sample selection. The researcher manually excluded the irrelevant papers which are either review articles, papers written in languages other than English or not directly related to literacy learning in educational settings. After the second round of data selection, a final database of 94 high-quality papers on academic literacy research within the time span between 2002 and 2019 were generated. However, considering the time of observation in this study, only researches conducted before October 2019 were included, which leads to a slight decrease in the total number of researches accounted in that year.

Coding procedure

Coding of the study was conducted from multiple perspectives. Firstly, the study specified three different approaches to academic literacy study based on their different understandings and conceptualizations of the construct (Allison & Harklau, 2010). Based on this initial classification, the study then conducted a new round of coding on the definitions of academic literacy, research methods, settings within each approach to look for possible interactions. Finally, a quantitative keywords frequency analysis was conducted in respective approaches to reveal the possible similarities and differences in their research focus. Specific coding criteria are specified as the following.

Firstly, drawing from Allison and Harklau (2010), the study classified all the researches in the database into three broad categories: language, disciplinary and sociocultural. While the language approach mainly focuses on the development of general or disciplinary-specific academic language features (Hyland, 2008), the disciplinary approach views academic literacy development as deeply embedded in the inquiry of disciplinary-specific values, cultures and epistemologies and can only be achieved via individual’s active engagement in disciplinary learning and inquiry practices (Moje, 2015). The sociocultural approach, largely influenced by the ‘academic literacies’ model (Lea & Street, 1998) contends that academic literacy development entails more than individual socialization into the academic community but is also closely related to issues as power, identity and epistemology (Gee, 2015; Lillis, 2008).

Based on this initial coding, the study then identified the research methods in all studies within each approach as either quantitative, qualitative or mixed method. Drawing from Creswell (2014), quantitative research is defined as ‘an approach for testing objective theories by examining the relationship among variables’ (p. 3) and is often quantified or numbered using specific statistical procedures. The use of this approach in academic literacy studies are often closely associated with corpus-driven text analysis, developmental studies, academic language assessment or large-scale intervention studies. This approach is particularly useful in unveiling the possible developmental effects of effective interventions but may fall short to account for the process of development which are often highly idiosyncratic and contextual. The use of qualitative methods can to some extent address this concern, as they often intend to explore deep contextualized meanings that individuals or groups ascribe to a social problem (Creswell, 2014). Drawing from the notion of literacy learning as a social practice, qualitative methods and especially linguistic ethnographies are highly encouraged in early academic literacy studies for their potential to provide detailed descriptions of a phenomenon through prolonged engagement (Lillis, 2008). In complementary, the use of mixed methods integrates both quantitative and qualitative data to ‘provide a more complete understanding of a research problem than either approach alone’ (Creswell, 2014, p. 3). This approach embodies huge potentialities in academic literacy research as it can align teaching and learning processes with possible developmental outcomes, which not only preserves the contextualized and practice-oriented nature of academic literacy research but also makes their results generalizable.

Secondly, the study classified all the researches into two types: interventionistic and descriptive. The former entails an intentional pedagogical intervention with an aim to improve individual and community learning practices. The latter, however, tends to adopt a more naturalistic approach under an intention to unveil the complex and dynamic interactions between academic literacy development and the wider sociocultural context. These two approaches complement each other in academic literacy researches in real educational settings, serving distinct purposes.

Thirdly, for a closer inspection of the context of research, the study specifies three general research settings: English as a native language (ENL), English as a second language (ESL) and English as a foreign language (EFL) (Kirkpatrick, 2007). According to Kirkpatrick (2007, p. 27), ‘ENL is spoken in countries where English is the primary language of the great majority of the population’ where ‘English is spoken and used as a native language’. ESL in contrast, ‘is spoken in countries where English is an important and usually official language, but not the main language of the country’ (Kirkpatrick, 2007, p. 27). These are also countries that are previously colonized by the English-speaking countries, often with a diverse linguistic landscape and complicated language policies (Broom, 2004). Therefore, language choices in these countries are often closely connected to issues as power, identity and justice. Academic literacy development in this respect serves both to guarantee social resource distribution and to empower individuals to change. Finally, ‘EFL occurs in countries where English is not actually used or spoken very much in the normal course of daily life’ (Kirkpatrick, 2007, p. 27). Within these settings, for example in China, English language education used to serve only for its own purposes (Wen, 2019). However, dramatic changes have been going on these days in pursuit of a language-content integrated curriculum to achieve advanced literacy and cognitive skills development. (Zhang & Li, 2019; Zhang & Sun, 2014).

Finally, the study conducted detailed keywords analysis in terms of their frequency within each approach (language, disciplinary and sociocultural). Based on these, the researcher then merged the raw frequencies of similar constructs for example: testing and assessment, teaching and pedagogy to get a better representation of the results. This analysis reveals the focus of research within each approach and helps promote further operationalization of the academic literacy construct.

The coding was conducted by two independent coders, with coder one in charge of the coding of all data, and coder two responsible for 30% of the coding of the total data. Coder one, also the main researcher trained coder two in terms of the coding procedures in detail with ample practices until the threshold of intercoder reliability was reached. Coder two then coded the remaining 30% of the data independently with an interrater reliability of over 80%. The coding was done on an excel worksheet which makes data access and retrieval readily available. The statistical software R was used for keywords frequency analysis.

Findings

Data analyses in the study mainly involve three parts: (1) specifying the construct and operationalization of the academic literacy research; (2) investigating the dynamic interactions among research approaches, methods and settings; (3) identifying the focus of research within each approach through keywords analysis. The following parts deal with these questions respectively.

Definition and operationalization of the academic literacy construct

The study extracted all the explicit definitions of academic literacy within each approach (language, disciplinary and sociocultural) and conducted detailed thematic analysis recategorizing them into different themes (see Table 1).

Table 1 shows that the definitions of academic literacy vary with respect to the different conceptualizations and epistemologies of academic literacy development within each approach. For instance, the language-based approach mainly defines academic literacy from two aspects: (1) language use in academic settings; and (2) language competence required for academic study (Baumann & Graves, 2010; Sebolai, 2016). The former takes a relatively narrow view of academic literacy development as learners’ gradual appropriation of the linguistic and rhetorical features of the academic discourse (Schleppegrell, 2013; Uccelli et al., 2014). The latter in complementary specifies academic literacy development for content learning purposes, entailing the kind of competence students need to possess for academic study (Kabelo & Sebolai, 2016). Academic language learning in this sense does not serve for its own sake but is considered as a tool for content learning and cognitive development. Overall, the language-based approach to academic literacy development lays much emphasis on the acquisition of academic language features which serves as a prerequisite for learners to examine and explore the meaning-making potential of the academic language (Schleppegrell, 2013).

The disciplinary-based approach on the other hand focuses on an integrated development of advanced language and cognitive skills within the disciplines, with language learning closely intertwined with the appropriation of disciplinary-specific values, cultures and practices. In this sense, academic literacy development is viewed as a dynamic process of higher-order language socialization in pursuit of deep, collaborative contextual meaning (Lea & Street, 2006). During this process, academic literacy development goes hand in hand with cognitive development and knowledge production within the disciplines, along with learners’ gradually expanding involvement with the disciplinary-specific ways of doing knowing and thinking (Granville & Dison, 2005). Other researches within this approach regard academic literacy development as more than language socialization but widely shaped and constrained by issues of power, epistemology and identity (Lea & Street, 1998). This definition is also widely used in the sociocultural approach, regarding academic literacy development as a sociocultural enterprise, widely related to the identification, reification and transformation of the social practices (Wenger, 1998).

The sociocultural approach also known as the ‘academic literacies’ model views literacy learning at the level of power struggle, structure reconstruction and social justice (Gee, 2015). Academic literacy development in this sense is not only a shared repertoire for individual access to social communities but also a tool for emancipation and transformation, which is object-oriented, practice-driven and value-laden (Lillis & Scott, 2007).

Academic literacy research approaches, methods and settings

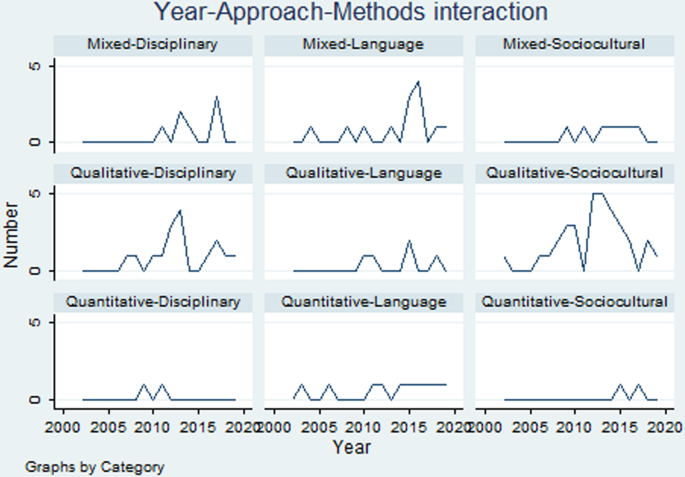

The study also analyzed changes in the approaches, methods and settings of academic literacy research over the past twenty years. Table 2 and Fig. 1 in the following present the number of quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies within the language-based, disciplinary-based and sociocultural approach respectively.

Table 2 and Fig. 1 show that the research methods chosen tend to vary with the approaches. To begin with, the number of qualitative studies generally surpassed the quantitative ones in both the disciplinary and the sociocultural approach, especially in the latter where qualitative studies dominated. However, their numbers tended to decrease in the past five years giving way to the rising mixed method researches. This was particularly evident in the growing number of mixed-methods language and disciplinary studies observed after 2015, which can also be an indication of the emergence of more robust designs in relevant educational researches. Finally, while the sociocultural approach was mainly featured by qualitative research, research methods in the language approach were more evenly distributed, which can possibly be accounted by its relatively longer research tradition and more well-established research practices.

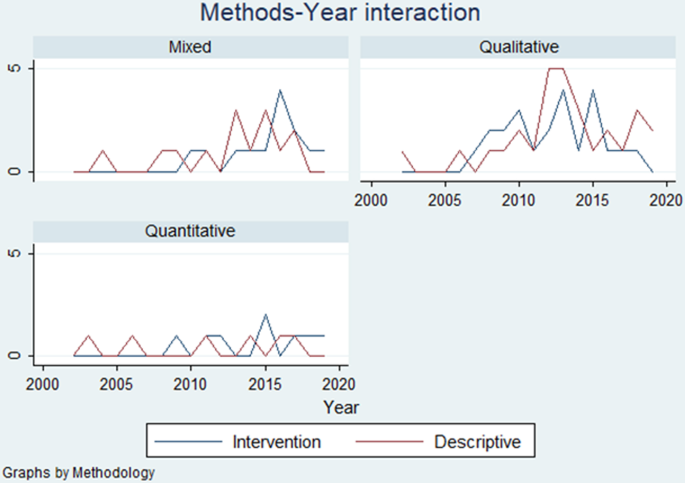

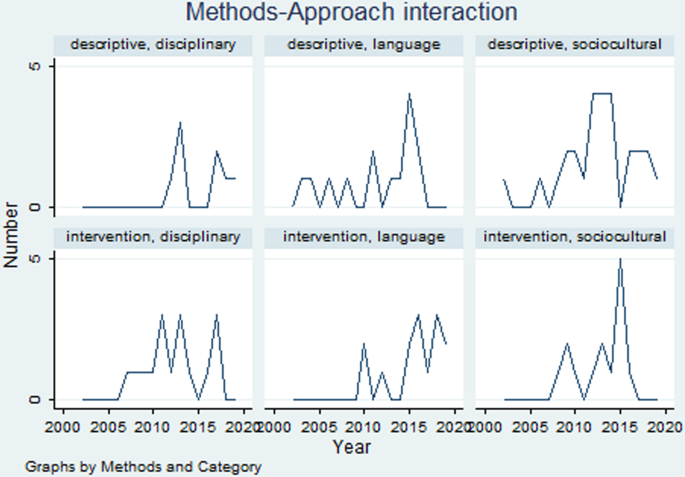

In addition, the study also specified changes in the number of descriptive and intervention studies each year (see Table 2, Fig. 2). Results showed that: (1) generally there were more qualitative researches in both the intervention and descriptive approach compared to the quantitative ones, although their numbers decreased in the past five years, especially in terms of the number of qualitative intervention studies; (2) a growing number of mixed-methods intervention studies were perceived in recent years. The findings echoed Scammacca et al.’s (2016) a century progress of reading intervention studies, indicating the emergence of more ‘standard, structured and standardized group interventions’ with ‘more robust design’ compared to the previous ‘individualized intervention case studies’ (p. 780). This developmental trend can indicate a possible methodological shift towards more large-scale intervention studies in the future based on recursive and reflective pedagogical practices. For more detailed descriptions of the methods-approach interaction, the study further investigated changes in the number of descriptive and intervention studies within each approach (see Table 3, Fig. 3).

Table 3 suggests that while the sociocultural approach tended to be more descriptive, the language and disciplinary approaches were more likely to interventionist. Another developmental trend was a dramatic decrease in descriptive language studies after 2015, giving way to an evident increase in intervention studies. This phenomenon entails an intricate connection among academic literacy development, education and pedagogy, indicating that language socialization does not come naturally, and well-designed, explicit pedagogical interventions are often in need.

Furthermore, the study tracked diachronic changes in the settings of academic literacy research. Results show that among the 94 selected academic literacy researches, 81 take place in a higher education context, accounting for about 86% of the total. Only 10 out of the 13 remaining researches take place in secondary school settings and 3 in elementary school settings. These results suggest that up-till-now, discussions on academic literacy development are mainly restricted to higher education settings, closely linked to the learning of advanced language and thinking skills. However, future researches may also need to attend to academic literacy development in secondary or primary school settings, especially in face of the growing disciplinary learning demands for adolescents (Dyhaylongsod et al., 2015).

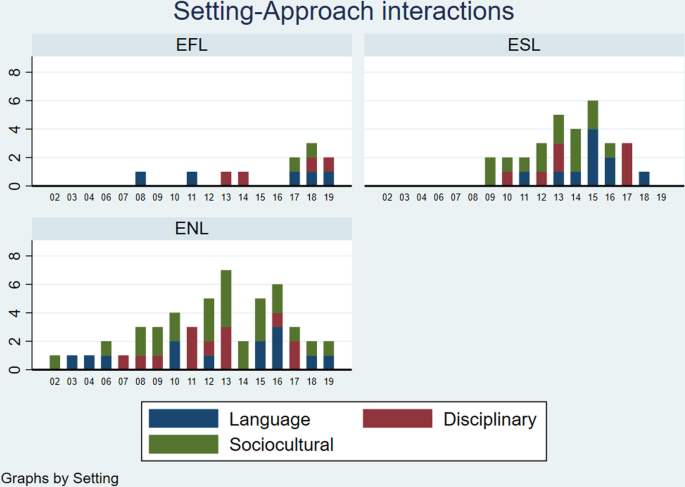

Finally, the study recorded the specific countries where academic literacy studies take place, among which South Africa stands as the highest with 22 studies amounting to 20.95% of the total, followed by the United States (17.14%), United Kingdom (12.38%), Australia (11.43%) and China (9.64%). These results suggest that academic literacy research most often take place in ENL or ESL settings with relatively long traditions of literacy teaching and learning, and prominent demands for academic literacy development within subject areas. In the meantime, the study attributes the high number of academic literacy research in the South African context to its complex linguistic realities and historical legacies, where literacy development is closely associated with issues of power, identity and equality (Broom, 2004; Lea & Street, 2006). Based on this, the study specified the approaches of academic literacy research within the ENL, ESL and EFL settings respectively (see Table 4, Fig. 4).

Table 4 shows that while the ENL settings dominated most of the academic literacy researches, relevant studies in ESL and EFL settings gradually increased in recent years, indicating an expanding influence of the academic literacy construct in different educational settings. Another pattern was the observation of more balanced research approaches or more evenly distributed language, disciplinary and sociocultural researches in all three settings. This phenomenon suggests that there seems to be an increasing flexibility in academic literacy research in recent years under the intention to address specific contextual issues. All these developmental trends reinforce the notion of academic literacy as a multi-dimensional construct (Cumming, 2013).

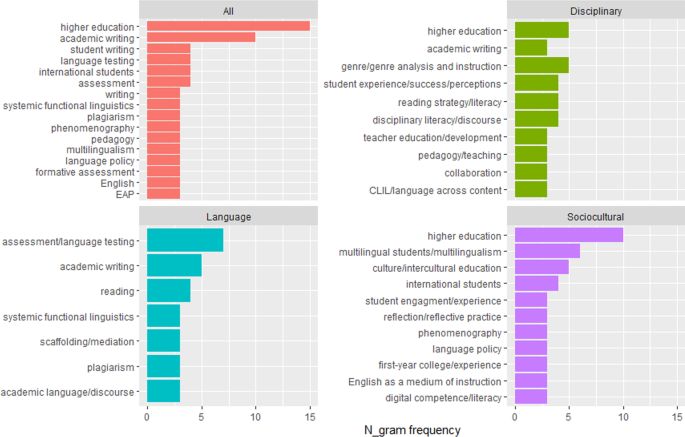

Focus of academic literacy research

To investigate the focus of academic literacy research within each approach, the study conducted detailed keywords analysis in all studies (see Fig. 5). Results show that academic literacy development is a situated educational practice, closely linked to issues as content learning, teacher education, assessment and pedagogy. Another feature that stands out is the frequent appearance of ‘writing’ and its related practices, such as: academic writing, student writing etc. This phenomenon suggests that compared to reading, writing seems to share a greater emphasis in academic literacy research. This can possibly be accounted by the intricate connections among writing, language and content learning and the gradual shift of focus from learning to write to writing to learn in higher education settings (Prain & Hand, 2016).

From Fig. 5, it can be seen that different approaches share common and distinct research focuses. For instance, the disciplinary approach is mainly featured by content learning and the development of subject-matter knowledge and skills, with a close relation to situated educational practices as genre and pedagogy, disciplinary-specific teaching and learning, reading interventions and teacher education. The language approach on the other hand tends to be more text-oriented, focusing on the development of advanced cognitive and academic language skills, widely influenced by the notions of Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) and genre pedagogy. In addition, assessment and testing are also a key issue in the language-based approach, indicating that language testing practices today are still largely text-oriented, focusing on the acquisition of specific academic language skills. Finally, keywords analysis results in the sociocultural approach revealed its deeply held assumptions of academic literacy development as a situated, complex sociocultural practice. One emerging feature is its growing attention to multilingualism, multiculturalism and international students. In an era of rapid globalization and academic exchange, academic literacy development has gradually become a global issue as is manifested in a rapid expansion of international students in ENL countries (Caplan & Stevens, 2017). These students, however, often face double barriers in language and content learning, especially in terms of advanced literacy skills development required for content learning and inquiry (Okuda & Anderson, 2018). In this sense, more attentions are needed for the implementation and innovation of effective community learning practices.

Discussion

Data analysis results in the study reveal that: (1) academic literacy development is a multidimensional construct (Cumming, 2013); (2) there is a growing number of mixed-methods intervention studies in recent years especially within the language approach; (3) a gradual expansion of academic literacy research in ESL and EFL settings is perceived with increasing attention to international and multilingual students. The following parts of the discussion and conclusion will provide detailed analyses on these aspects.

Definition and keywords analysis of the academic literacy studies reveal that academic literacy is a multidimensional construct, embodying both textual and contextual practices and bears huge significance for individual language and cognitive development. Drawing from this, future researches may need to cross the boundaries to integrate the language, disciplinary and sociocultural aspects of academic literacy development within a holistic view of literacy teaching and learning. In this respect, academic literacy development can widely draw from various research domains as language acquisition, language socialization, genre and pedagogy and critical literacy (Duff, 2010; Gee, 2015; Hyland, 2008; Lea & Street, 2006; Russell, 2009). Future researches may need to pay more attention to these multiple aspects which closely intertwine and mutually shape one another to serve for the innovation and design of effective practices.

Data analysis in the study also demonstrated the intricate connections between literacy learning and pedagogical interventions. The development of academic literacy does not come naturally, but often calls for explicit instruction and interventions to address situated learning needs (Shanahan, 2012). It is hoped that in the future larger-scale interventions with more rigorous designs are necessary in pursuit of more effective pedagogical practices (Scammacca et al., 2016). This assumption, however, are not in contradiction to the dynamic and contextual nature of academic literacy development, as more sophisticated designs can generally provide more detailed account of the practice-driven and contextualized learning processes which are often cyclical and recursive in nature.

Lastly, results of the study revealed a growing trend of academic literacy research in EFL settings especially with respect to English language learners and international students. Compared to the ENL and ESL settings, academic literacy research in EFL settings, although a relatively recent issue, embodies huge potentialities. Drawn by the demand to promote higher-order thinking and learning and the need to innovate traditional form-focused, skilled-based EFL pedagogy, the notion of academic literacy development as a disciplinary-based, socioculturally constructed, dynamic academic socialization process offers a sensible option for pedagogical innovation and curriculum development in these contexts. In this sense, the notion of academic literacy as a multidimensional construct has provided a possible solution to the long-standing problems concerning the efficacy the efficiency of EFL education, the alignment of language and content learning as well as the challenges in curriculum design and material development in EFL settings (Wen, 2019).

Conclusion and implication

Results of the study suggest a relatively straight-forward agenda for the development of effective academic literacy pedagogies. Firstly, the study revealed an intricate connection between academic literacy development and disciplinary-specific knowledge construction and inquiry activities. Academic literacy development is by no means only a textual issue, but agentive scaffolded learning activities that are meaningful, purposeful and authentic. Literacy activities such as reading and writing in this sense are often object-oriented to serve for real knowledge production and communicative needs. Therefore, effective academic literacy instruction often aligns language development with content learning within meaningful disciplinary and social inquiries.

Secondly, in an era of rapid globalization and communication, the development of academic literacy often takes a critical role in resource distribution and power reconstruction. This has also led to an increasing attention to academic literacy development of international students in multilingual contexts, who often face multiple challenges in learning disciplinary literacy. However, contrary to the traditional ‘deficit model’ seeking for a remediation for their relatively ‘disadvantaged’ language background, the notion of academic literacy highlighted the role of teacher and learner agency in the development of new pedagogical practices. These innovative approaches often acknowledge and build on students’ diverse language and cultural backgrounds to make literacy learning a cognitively meaningful and culturally valuable practice.

The study can shed light on future research from both an empirical and pedagogical perspective. From an empirical perspective, future research may need to pay more attention to the multidimensionality of the construct of academic literacy. As revealed in the current study, academic literacy development embodies multiple dimensions as language learning, cognitive development and social transformation. Future research may need to transcend the epistemological boundaries to seek for a more integrated definition of academic literacy in which language, cognitive and social development mutually transform one another. From a pedagogical perspective, an activity-based, integrated pedagogy should be proposed in academic literacy development. In the case, students generally use language to engage in authentic communication and practices relating not only to the advancement of disciplinary knowledge but also for the betterment of society. As it is through these practices that students’ engagement in complex meaning making and higher order thinking are ensured, and the internalization of language knowledge and transformation of social practices gradually occur.

The study also bears some limitations. Although it seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of the general trend, method and focus of academic literacy research for nearly two decades, it does not go deeper into specific studies of their findings and implications. Future studies can possibly narrow down their scope of investigation to delve deeper and provide a more thorough analysis of specific research findings.

Availability of data and materials

The studies reviewed can be referred from the reference citations in the supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

- CALLA:

-

Cognitive Academic Language Learning Approach

- DDL:

-

Data driven learning

- EAP:

-

English for Academic Purposes

- ENL:

-

English as a native language

- ESL:

-

English as a second language

- ESL:

-

English as a second language

- SFL:

-

Systemic Functional Linguistics

- SIOP:

-

Sheltered Instruction Observation Protocol

References

Allison, H., & Harklau, L. (2010). Teaching academic literacies in secondary school. In G. Li & P. A. Edwards (Eds.), Best practices in ELL instruction. The Guilford Press.

Anthony, L. (2017). Introducing corpora and corpus tools into the technical writing classroom through Data-Driven Learning (DDL). In J. Flowerdew & T. Costley (Eds.), Discipline-specific writing: Theory into practice. Routledge.

Bailey, A. L., Butler, F. A., Stevens, R., & Lord, C. (2007). Further specifying the language demands of school. In A. L. Bailey (Ed.), The language demands of school: Putting academic English to the test. Yale University Press.

Basturkmen, H. (2017). Developing writing courses for specific academic purposes. In J. Flowerdew & T. Costley (Eds.), Discipline-specific writing: Theory into practice. Routledge.

Baumann, J. F., & Graves, M. F. (2010). What is academic vocabulary? Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(1), 4–12.

Bigelow, M., & Vinogradov, P. (2011). Teaching adult second language learners who are emergent readers. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 31, 120–136.

Broom, Y. (2004). Reading English in multilingual South African primary schools. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7(6), 506–528.

Caplan, N. A., & Stevens, S. G. (2017). “Step out of the cycle”: Needs, challenges, and successes of international undergraduates at a U.S. University. English for Specific Purposes, 46, 15–28.

Chamot, A. U., & O’Malley, J. M. (1987). The cognitive academic language learning approach: A bridge to the mainstream. TESOL Quarterly, 21(2), 227–249.

Charles, M. (2013). English for academic purposes. In B. Paltridge & S. Starfield (Eds.), The handbook of English for specific purposes (pp. 137–155). Wiley-Blackwell.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

Cumming, A. (2013). Multiple dimensions of academic language and literacy development. Language Learning, 63(1), 130–152.

Duff, P. A. (2010). Language socialization into academic discourse communities. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 169–192.

Dyhaylongsod, L., Snow, C. E., Selman, R. L., & Donovan, M. S. (2015). Toward disciplinary literacy: Dilemmas and challenges in designing history curriculum to support middle school students. Harvard Educational Review, 85(4), 587–608.

Echevarria, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D. J. (2013). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP model. Pearson Education.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Cambridge University Press.

Engestrom, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. In R.M.R.-L.P. Yrjo Engestrom (Ed.), Perspectives on activity theory. Cambridge University Press.

Fang, Z. (2012). Approaches to developing content area literacies: A synthesis and a critique. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(2), 103–108.

Fang, Z., & Coatoam, S. (2013). Disciplinary literacy: What you want to know about it. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(8), 627–632.

Fisher, R. (2019). Reconciling disciplinary literacy perspectives with genre-oriented Activity Theory: Toward a fuller synthesis of traditions. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(2), 237–251.

Flowerdew, J. (2013). Introduction: Approaches to the analysis of academic discourse in English. In J. Flowerdew (Ed.), Academic discourse. Routledge.

Gebhard, M. (2004). Fast capitalism, school reform, and second language literacy practices. The Modern Language Journal, 88(2), 245–265.

Gee, J. P. (2015). Literacy and education. Routledge.

Goldenberg, C. (2010). Improving achievement for English learners: Conclusions from recent reviews and emerging research. In G. Li & P. A. Edwards (Eds.), Best practices in ELL instruction (pp. 15–44). The Guilford Press.

Granville, S., & Dison, L. (2005). Thinking about thinking: Integrating self-reflection into an academic literacy course. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 4, 99–118.

Halliday, M. A. K. (2000). An introduction to functional grammar. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press.

Hyland, K. (2008). Genre and academic writing in the disciplines. Language Teaching, 41(4), 543–562.

Kirkpatrick, A. (2007). World Englishes: Implications for international communication and English language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157–172.

Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (2006). The “Academic Literacies” model: Theory and applications. Theory into Practice, 45(4), 368–377.

Lillis, T. (2008). Ethnography as method, methodology, and “deep theorizing” closing the gap between text and context in academic writing research. Written Communication, 25(3), 353–388.

Lillis, T., & Scott, M. (2007). Defining academic literacies research: Issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 5–32.

Lillis, T., & Tuck, J. (2016). Academic literacies: A critical lens on writing and reading in the academy. In K. Hyland & P. Shaw (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of English for academic purposes (pp. 30–44). Routledge.

Lillis, T., & Turner, J. (2001). Student writing in higher education: Contemporary confusion, traditional concerns. Teaching in Higher Education, 6(1), 57–68.

Moje, E. B. (2015). Doing and teaching adolescent literacy with adolescent learners: A social and cultural enterprise. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 254–278.

Moje, E. B., Overby, M., Tysvaer, N., & Morris, K. (2008). The complex world of adolescent literacy: Myths, motivations, and mysteries. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 107–154.

Okuda, T., & Anderson, T. (2018). Second language graduate students’ experiences at the writing center: A language socialization perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 52(2), 391–413.

Prain, V., & Hand, B. (2016). Coming to know more through and from writing. Educational Researcher, 45(7), 430–434.

Russell, D. R. (2009). Texts in contexts: Theorizing learning by looking at genre and activity. In R. Edwards, G. Biesta, & M. Thorpe (Eds.), Rethinking contexts for learning and teaching: Communities, activities and networks. Routledge.

Scammacca, N. K., Roberts, G. J., Cho, E., Williams, J., Roberts, G., Vaughn, S. R., et al. (2016). A century of progress: Reading interventions for students in grades 4–12, 1914–2014. Review of Educational Research, 86(3), 756–800.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2013). The role of metalanguage in supporting academic language development. Language Learning, 63(1), 153–170.

Sebolai, K. (2016). Distinguishing between English proficiency and academic literacy in English. Language Matters, 47(1), 45–60.

Shanahan, C. (2012). How disciplinary experts read. In T. L. Jetlon & C. Shanahan (Eds.), Adolescent literacy in the academic disciplines: General principles and practical strategies. The Guilford Press.

Shanahan, T., & Shanahan, C. (2008). Teaching disciplinary literacy to adolescents: Rethinking content-area literacy. Harvard Educational Review, 78(1), 40–59.

Short, D. J., Echevarría, J., & Richards-Tutor, C. (2011). Research on academic literacy development in sheltered instruction classrooms. Language Teaching Research, 15(3), 363–380.

Short, D., & Fitzsimmons, S. (2007). Double the work: Challenges and solutions to acquiring language and academic literacy for adolescent English language learners—A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. Alliance for Excellent Education.

Street, B. (2003). What’s “new” in New Literacy studies? Critical approaches to literacy in theory and practice. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 52(2), 77–91.

Uccelli, P., Barr, C. D., Dobbs, C. L., Galloway, E. P., Meneses, A., & Sanchez, E. (2014). Core academic language skills: An expanded operational construct and a novel instrument to chart school-relevant language proficiency in preadolescent and adolescent learners. Applied Psycholinguistics, 36(5), 1077–1109.

Wen, Q. (2019). Foreign language teaching theories in China in the past 70 years. Foreign Language in China, 16(5), 14–22.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Wingate, U. (2018). Academic literacy across the curriculum: Towards a collaborative instructional approach. Language Teaching, 51(3), 349–364.

Zhang, L., & Li, D. (2019). An integrated development of students’ language and cognition under the CLIL pedagogy. Foreign Language Education in China, 2(2), 16–24.

Zhang, L., & Sun, Y. (2014). A sociocultural theory-based writing curriculum reform on English majors. Foreign Language World, 5, 2–10.

Zhao, K., & Chan, C. K. K. (2014). Fostering collective and individual learning through knowledge building. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 9, 63–95.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the original manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the start up research funding for young scholars in Nanjing Normal University (No. 184080H202A135).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, D. A review of academic literacy research development: from 2002 to 2019. Asian. J. Second. Foreign. Lang. Educ. 7, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-022-00130-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-022-00130-z